David Weakliem has a wonderful blog, Just the Social Facts, Ma'am. He's an expert on public opinion and routinely posts interesting descriptive analyses of trends on a variety of topics.

He recently posted a great series titled Lives of Despair. The goal is to assess whether deaths of despair among the US white working class, documented and popularized by the work of Case and Deaton, are preceded by lives of despair, or a general separation of feelings of malaise between whites in different class locations, roughly proxied by whether one has a college degree or not. Weakliem follows trends in a variety of attitudinal data from the General Social Survey (GSS) and assesses how the white working class (WWC) differs from white respondents with a college degree. It's great stuff, I learned a lot and just loved it.

This post follows up with some minor methological adjustment that may help highlight some subtletly below the overall trends Weakliem documents.

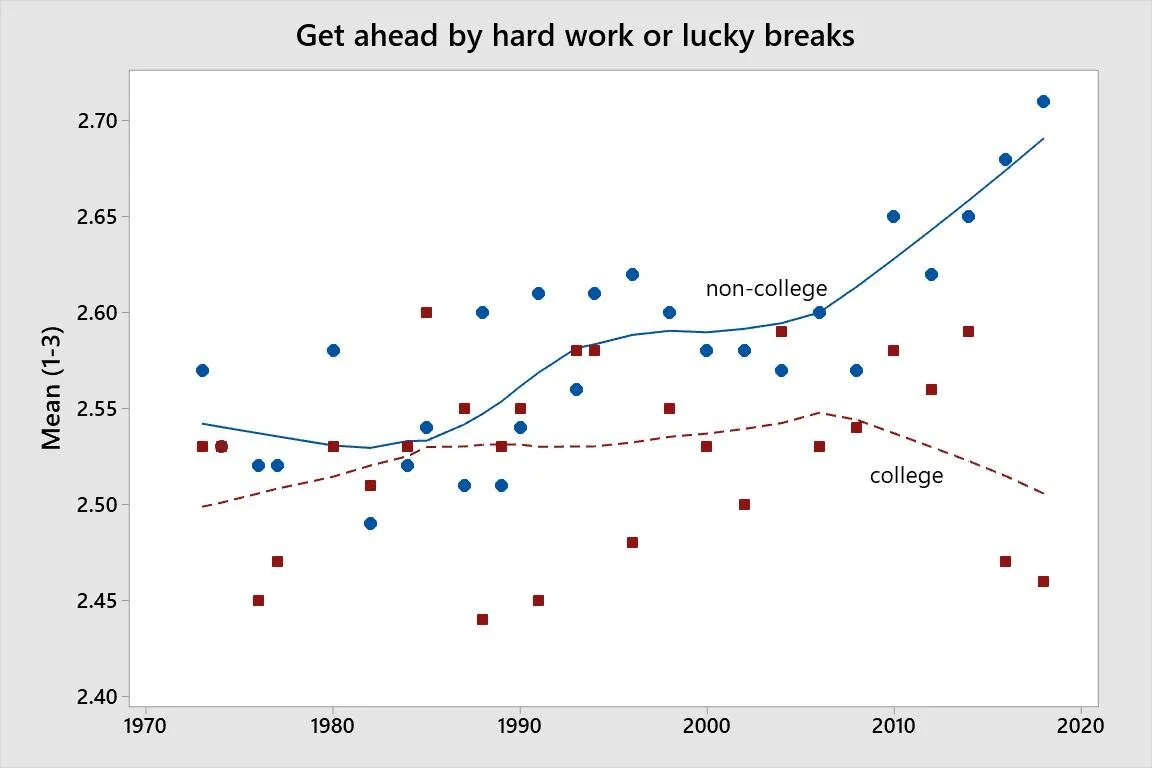

Let's begin by focusing on one specific attitudinal item, the getahead question asked by the GSS: "Some people say that people get ahead by their own hard work; others say that lucky breaks or help from other people are more important. Which do you think is most important?" Answer choices are: (1) Hard work (2) Both equally (3) Luck or help. Weakliem takes the mean responses by year and plots differences between white respondents with, and without, a college degree. Below are his results.

As you can see, views have recently diverged about how one gets ahead. Weakliem argues that the divergence began during the great recession.

What changes when you treat getahead as nominal?

The GSS variable getahead doesn’t look either very continuous or ordinal to me. And critically, basic tests of ordinality, such as the Brant test, suggest that a simple ordered logistic regression model with year contrasts interacted with a college-non college binary variable violates the parallel regression assumption (Chi square value in the hundreds), which we need to think of these categories as ordered. This is all to say: the mean may be masking important nonlinear variation in trends across the categories. So let’s replicate Weakliem’s descriptive assessment using a simple multinomial logistic regression model and see if we can notice any additional relevant trends over time. Below are my results.

I plotted probabilities from the multinomial logit models for each of the three categories over time. A few things jump out to me:

For respondents with a college degree, probabilities for both the “Hard work” and “Both equally” categories remained pretty stable over time, while we see a fairly big jump in the “Luck or help” category in 2016 and 2018.

There’s no real action among the white working class (WWC) in the “Luck or help” category. No trend that I see.

We see a massive positive shift from about 2000 onward for the WWC in the “Hard Work” category (although you could argue it began in 1980). The probability of falling in this category increased from 0.65 in 2000 to 0.8 in 2018.

In 2016 and 2018, there’s a large drop in the probability of “Both” among the WWC, from about 0.2 to 0.1.

So what are the big points? (1) It looks like something around 2016 caused massive polarization in views about “Luck” between higher and lower educated people. (2) The WWC has been growing in its belief in “Hard Work” since 2000. This growth appears to have predated the Great Recession.

OK this is getting fun!! Let’s take a look at marginal effects of education over time across the three categories. These may better illustrate gaps between classes over time. Below we look at differences in the probabilities for each getahead category between the WWC and those with a college degree, separately by year. Values above zero indicate that WWC have a higher probability of falling into this category. Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals.

The WWC had a pretty persistent higher probability of choosing “Hard Work,” especially from the mid-1990s and onward. We then saw sizable growth of this gap in 2016 and 2018, the first time where the marginal effect was at or above 0.15 for 2 straight waves.

College educated folks consistently had higher probabilities of “Both” from the 1990s onward. By now, the difference is looking fairly entrenched.

We see a college / WWC gap for “Luck” emerge for the first time in 2016 and 2018.

It’s also interesting that we observe few consistent education differences in the 1970s and 1980s. Educational polarization is a fairly recent phenomenon, occurring during and after the Clinton administration.

So taken all together: the gap in viewpoints about getting ahead between those with a college degree and the WWC has been around since the mid-1990s. The WWC has become distinct in its privileging of hard work since around 2000. And it seems that polarization around luck/help emerged in 2016.

Why is this happening? Good question. I’m not sure yet. Here are a few lingering questions I have:

What are cohort and age effects? My murky knowledge of work on the WWC is that the mortality occurs among the middle aged. Would we see these trends in that group? If these trends are driven by, say, seniors, then it’d be tough to connect them to a “lives of despair” argument.

Do views get locked into cohorts , or do they vary across age within cohorts over time?

To what extent are we seeing selection effects over time? Presumably those uncertain about how specifically to make it these days would probably try and go to college, because one of the few clear messages you hear about economic success is, “Go to college” (although there is some inaccurate pushback these days).

Are college graduates in the 1990s onward more likely to know the kinds of people who do, in fact, get ahead in life and have greater information to the pathways that resulted in making it? I know a few (not many) very affluent folks. Knowing what I know, I wouldn’t attribute all their rise to hard work.

Weakliem noted that the view of hard work among the WWC is tricky to reconcile with a lives of despair argument. I actually come down with somewhat of an opposite perspective. If you attribute success and failure mostly to your own efforts, well, then what do you make of life when the massive structural factors out of your control — computerization, union decimation, stagnating minimum wage, the China shock, resource hoarding among elites — all hit you in a span of two decades? It certainly feels like a depressing and mortifying combination of factors.