This weekend, I looked at some of the unpublished drafts for this blog. The one below stuck out to me. I fear it’ll be a more correct prediction than not.

From what I’ve observed, there’s a building consensus on the letter shape of the recovery from covid: k! That is, the pandemic destroyed the economic prospects and community of many already struggling workers and families, while proving to be either a bump in the road for Zoom-able knowledge workers or highly profitable for the most affluent. Way more raw materials for folk like myself who study growing inequality, sadly.

I think we’re going to see K’s everywhere we look. I’ll just briefly mention this as a detour of the post’s main point (in hopes of writing a bit more on it later), but school is an obvious example of an additional k-shaped recovery. Living in a large metro area, it’s been just wild to see national rhetoric along the lines of, “let’s just call this year a wash for our nation’s kids and reset next year” while observing that private schools are running on overdrive and public schools shut down. Like the economy, this won’t just be a lost year to make up next time. It’ll be a massive K-shaped inequality maker, with an additional year of education provided to those who could afford it.

I suspect that academics, as with the economy more generally, have experienced a K-shaped recovery from the pandemic. I know of several people who have never been more productive than in the last 10 months. I know of people who’ve nimbly reshifted their research interests to the inequalities surrounding the spread of a novel respiratory disease and picked up media and disciplinary notoriety.

Sadly, I also know others like myself, who’ve struggled with role strain during the pandemic. My youngest kid was two when the pandemic began, and if you’ve never cared for a two year old…let’s just say that with all the care work required to keep them from killing themselves, it’s a small miracle that our species has not gone extinct. Now there’s some good research coming out showing that, yup, there’s probably going to be a k-shaped recovery in the academy as well.

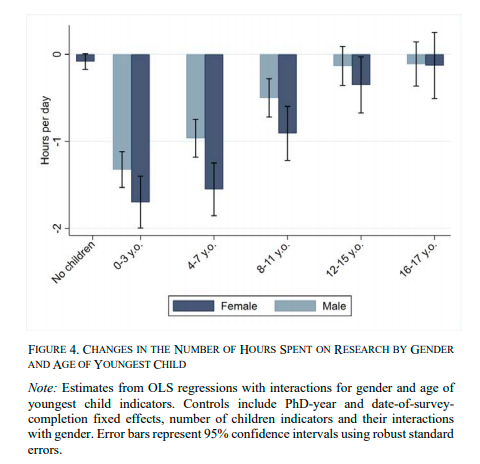

As the figures below show, there have been big gaps in research productivity created by the pandemic.

Rightly, lots of attention has been paid to the gender inequality covid has created. The general problems of gender inequality the pandemic has both created and revealed is such a massive social problem and national embarrassment. Female academics have had a much bigger hit to productivity than men, on average. But there’s also a parent effect. Folks without kids haven’t had a change to productivity, on average, while folks with kids, men and women, have.

It’s stratified by age of child too.

Young kids make for bigger productivity gaps. This is totally, totally obvious to me. At the beginning of the pandemic, a sociology superstar Maggie Frye voiced despair on twitter about the trials of raising young kids during a pandemic. If even Frye, one of the greatest young scholars in the discipline, is struggling, what hopes have the rest of us?

It’s important to note caveats. Because they abound. And they’re super, super real. If your parent (nearly) dies but you don’t have kids, you’ve also lost out, but that’s not shown in the aggregate results. If you have young kids but make bank and have a secret live-in nanny (a pretty frequent occurrence, via my observations), your research likely won’t take as big of a hit even if you’re in the danger group with me. Every teen and tween I know is really, really struggling with the lockdown. If your older child is depressed or suicidal, how can that be anything but debilitating for you? That isn’t shown in the aggregate numbers.

So group means aren’t destiny. But boy howdy, does that not look to you like the catalyst for a k-shaped recovery among academics?

For a long time, official messaging by academics has been wonderful. Many universities have extended tenure clocks and focused on how to support graduate students. This has been amazing. Universities didn’t need to do this. Senior folks didn’t need to be so generous. I’m spoiled because I’m in a department full of senior faculty who are ridiculously compassionate, intelligent, and proactive. With that said, I’m starting to see the “green shoots” at the university level of a transition from the “it’s ok to not be ok” logic of the pandemic to the “innovators know how to do more with less” phase.

If this is happening now, then what will the standards of evaluation be in three years, when the k-shaped catalysts of productivity make for much larger gaps? Will it even be fair at all to “downweight” folks who excelled during this time, or would such “downweighting” and “upweighting” of standards occur primarily within high-status communities, yielding additional advantages to folks like Ivy League connected academics? It’s all awful to think about. But I think my advice below was broadly correct, and I wish I had published it. You really should not have listened to the nice messaging, because I think that’ll be an ephemeral hit. The real action is between the arms of the k. And you’ve probably already been sorted.

A May 11 draft I did not publish:

The cost of kindness: productivity and a global pandemic

Earlier I discussed my strategies to keep going while investing a substantial amount of time into childcare. It kind of worked this semester. But goodness gracious, was this semester a drag on my productivity. I was able to keep a few projects slowly barely moving forward, mostly because of hard external deadlines and/or good collaborators. Yet I have only somewhat jokingly called this the “lost semester.” Transitioning courses online, maintaining service obligations, the added meetings, the childcare crunch, general existential worries, and trying to help my upset and isolated kids sucked up most of the oxygen of these past two months.

Online, academics have been wonderful. Many have publicly stated that it’s ok to slow down. Don’t hold unreasonable expectations for maintaining your research during these difficult days. Folks have been very accommodating to the toddlers joining meetings. Many universities have graciously extended the tenure clock by a whole year. These acts of kindness and forgiveness are very real, and they will do a lot of good.

However, I can’t help think that down the road, traditional standards and defaults will prevail, and that today’s kindness will simply dissolve into tomorrow’s disadvantage.

In three years, when promotion committees, granting agencies, external tenure letter writers, merit pay deciders, hiring committees, administrators, general givers-of-prestige (awards, fellowships, high status work-based vacations) etc., look at a stack of CVs, how likely do you think they will follow through on a complex scheme of discounting and reweighting standards to address the fact that some folks could, and did, lean into productivity during a pandemic, some folks technically could but had external reasons not to, and others were swamped with childcare responsibilities that essentially ground their lives to a halt? Or how likely do you think decision makers will simply reach for the standard set of tools identifying excellence and top performers, selecting those?

I’m not a betting man, but if I had to put money down, it would definitely, definitely be on the latter.

But I think it might be worse: what if they do adjust for this complex bundle? How in the world would one do so? My hunch is that advantage would be accrued through social networks and preexisting markers of status, akin to the concerns voiced by those fighting the tide of abolishing the SAT (e.g. without a test metric, un-meritocratic mechanisms win the day). My hunch is that rewards will be provided to an Ivy League professor with an au pair, not a visiting professor at East Western State U with two kids and a four-four course load.