The sociologist Philip Cohen routinely publishes the gender composition of articles published in two flagship journals of sociology, American Sociological Review (ASR) and American Journal of Sociology (AJS).

Below he discusses the recent distribution of authorship by gender.

And here are the distributions for our flagships, by his count.

There’s an especially large gender imbalance in AJS authorship. Sociology has become a majority female discipline, I believe, which further underscores the problems associated with the observed compositions Cohen documents. Of course, management, business, political science, applied researchers, and even the occasional economist publishes in AJS, so you can’t lock in your reference group exclusively to sociology. But the caveats are pretty minor compared to the major trends Cohen documents, I figure.

In the comments below his tweet, he and other sociologists lambast AJS for its skewed gender distribution of authorship. Cohen mentions that he boycotts reviewing manuscripts for, and submitting to, AJS. That’s a bummer. Cohen has published really, really good research in AJS before, so his boycott is a loss for the discipline. Others mention similar decisions.

Now, Cohen is an amazing sociologist. I admire his moral compass, he has published a heck of a lot of extremely important research, his blog is awesome and important, he does fantastic public sociology work, and he has done a whole lot to move sociology to open access transparency. On most every important topic, I find myself in agreement with him, and in admiration of his use of the academic career. But I think that for this point, specifically, the focus of his attention may be a tad off.

Wait, what!? But look at those gender differences in publications! Do I think that gender inequality is unimportant? Am I part of a (relatively) new generation of gender discriminatory sociologists who will continue to perpetuate unequal opportunity in the field? I hope not. Let me try and convince you that the problem isn’t the gender composition inside the current pie…but the size of the pie itself. We’d do better for research done by women sociologists, and really all sociologists, by growing our flagship pie, even if we accepted the current imbalanced gender ratio.

My thinking is motivated by a blog post by Sam Altman, in which he discusses the problems of low or zero economic growth. Long story short…low growth is really, really bad. It creates a bunch of bad incentives. It creates zero-sum competition within the low growth world, it means that standing up for yourself necessarily means standing on the toes of another. Growth makes for pressure release, it allows for more winners, and more feeling of winning. You can ask for yours without necessarily taking it from someone else. Low/no growth has been the situation the US has found itself in for awhile. But it gets worse, as it so often does. Since Altman wrote, Piketty, Saez, and their team have shown that virtually all of the economic growth of the United States has gone to upper-income earners since the 1980s. No wonder the US social fabric seems to be fraying.

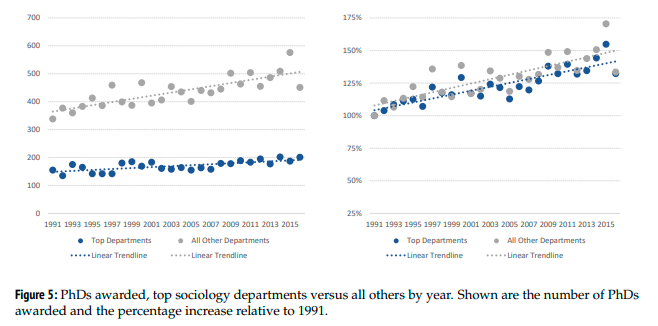

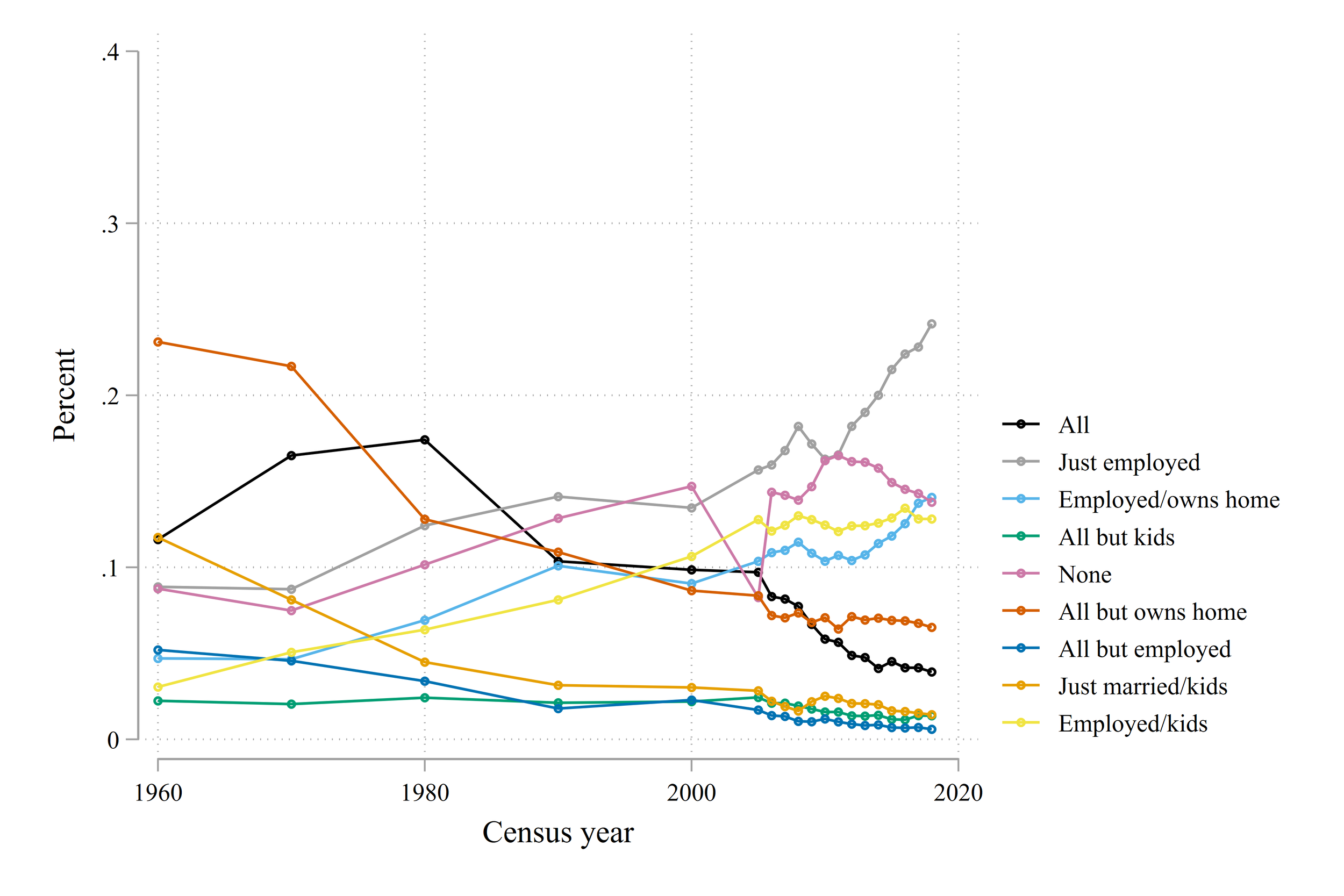

Let’s get this back to sociology. So I’m arguing that we shouldn’t focus on the gender balance of AJS and ASR? Well, I guess that I’m specifically arguing not to do so at first. I’d say that such a focus is very downstream from more fundamental problems of stagnation among our flagship journals. To motivate this point, let’s take a look at some great descriptive work by Rob Warren in his 2019 article in Sociological Science, “How Much Do You Have to Publish to Get a Job in a Top Sociology Department? Or to Get Tenure? Trends over a Generation.” Below is his visualization of the change in PhDs awarded in sociology between 1991 and 2015.

What are we looking at here? The left panel shows the absolute number of PhDs awarded, in top departments and all other departments. The right panel shows changes relative to 1991. I find the right panel a bit more intuitive to follow. We are producing more people with sociology PhDs today than we did in 1991. Specifically, the number of sociology PhDs awarded in 2015 was 50% higher than the number in 1991.

This means a few things. There are probably more graduate students prior to this awarding of PhD status. There are more people trying to get jobs. There are probably more people probably trying to publish articles.

What has happened to job availability over time? If you’re a graduate student, brace yourself:

Data visualization comes from Jeff Lockhart. So…the great recession was really bad for the job market. Tenure track jobs declined from 724 in 2006 to 299 in 2009. The market never recovered, peaking at 526 positions advertised, and has functionally disappeared this year. So…more competition?

What about publishing expectations? Back to Warren’s article. Warren shows that these have increased as well.

The top numbers indicate the number of publications people brought into their first year as an AP (left panel) and the number of articles published when folks became associate professors (right panel). The clear white boxes are a little funky…these are “all other publications,” which include “short commentaries, replies to short commentaries, book reviews, editorials, introductions to special issues, letters to the editor” along with textbooks and edited volumes. These are tricky value judgments.

I’d focus most on the bottom gray and blue bars to get a sense of the magnitude of rising standards. These are the bread and butter of tenure evaluation: article publications. You can see that while folks brought in about 2.5 articles in 1991, they’ve brought in about 4.8 articles by 2017. Graduate student publishing expectations have increased by about 90% since 1991. Whereas folks were promoted with about 6.4 articles in 1991, they were promoted with about 11.1 articles in 2017. Publishing expectations have increased by about 75% on the tenure track. You should really read the whole Warren article. It’s awesome. He’s awesome. But in absolute numbers: pre-PhD publication expectations have increased by about 2 articles, and tenure expectations have increased by about 4.5 articles. Not a small change. Publishing takes a long time.

This is the point where I start to disagree with Cohen. What has happened to the productivity of our top journals? I haven’t heard this point discussed this way, so let me rephrase it: to what extent has the number of articles published annually in our flagships been keeping apace with [i] the increase in the stock of sociologists [ii] increased publication expectations to get jobs [iii] increased publication expectations to get promoted [iv] increased pressure to be productive early in a more competitive world of greater scarcity? I never really thought about this question, but I’d assumed that the journals were growing over time, but not at the pace of publishing expectations or PhD production. Right now, what are your assumptions? Are ASR and AJS publishing more, the same, or less than in the 1990s?

…

…

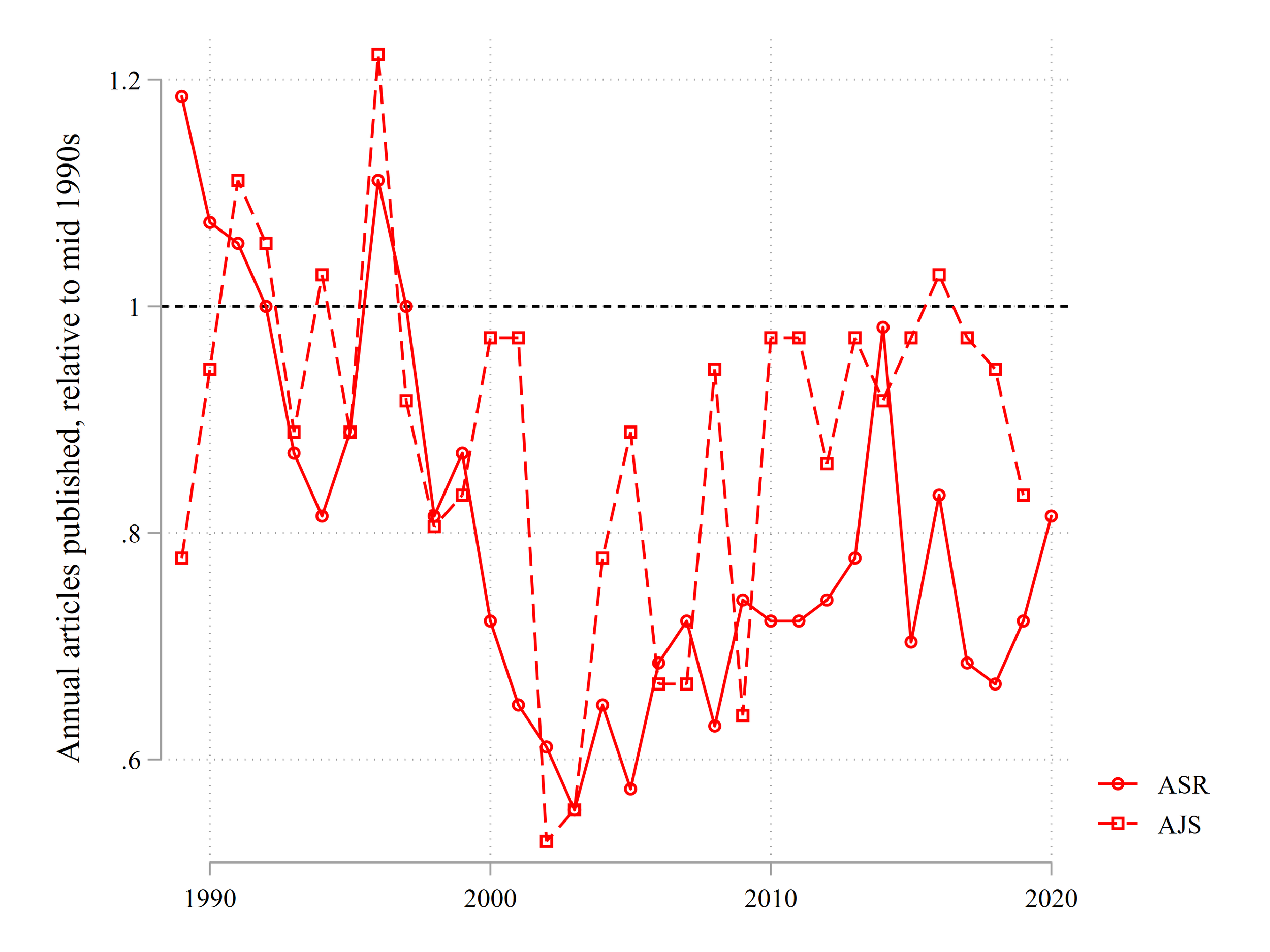

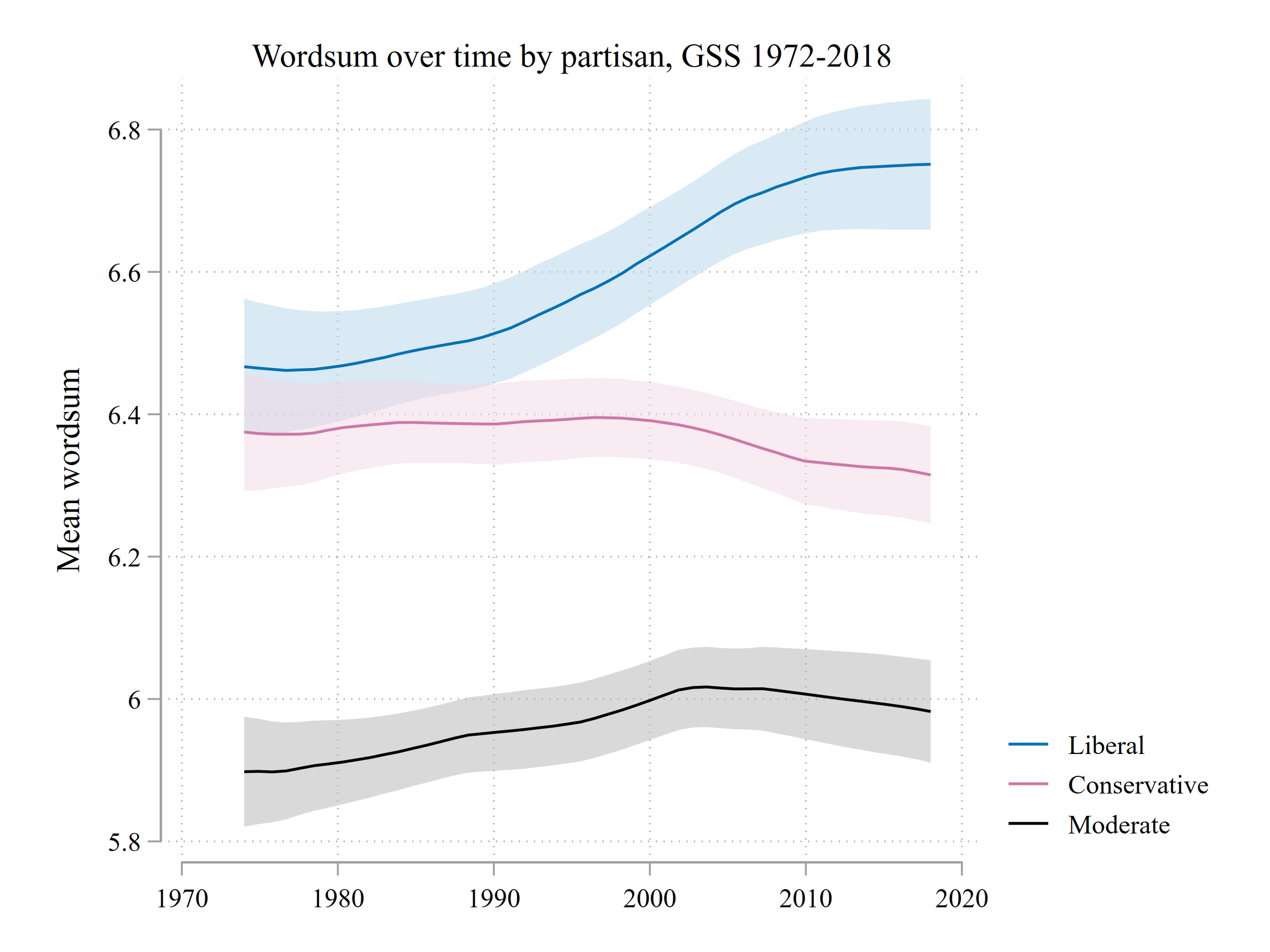

My assumptions were wrong. The figure below shows the number of articles that show up for ASR and AJS per year. I collected these from Web of Science. I did it quickly, so be wary. Trust the numbers only to the extent you trust Web of Science. I spot checked two years (1995 and 1996) but not the rest. I looked only at articles and preceding papers. I excluded things like corrections, comments, letters, introductions, book reviews, etc. I believe AJS is still publishing its 2020 articles, so it stops at 2019.

…umm…what? The number of articles that ASR has published appears to have declined. ASR was publishing about 60 articles annually in the late 1980s. By the mid-2000s, that number was between 30 and 40!! AJS has been fluctuating between 20 and 40 articles annually.

Let’s look at the ratio of a year’s annual publications relative to the amount published in the mid-1990s (94, 95, 96).

Bonkers. AJS spent the 2000s publishing only 60% of the articles from the decade prior, while ASR is currently publishing about 80% of the articles that it published in the mid 1990s. Perhaps I’m messing something up, or perhaps Web of Science doesn’t count articles correctly. So read with appropriate skepticism. But it sure looks like our flagship journals have shrunk their pies by about 80% compared to what they were doing 25 years ago.

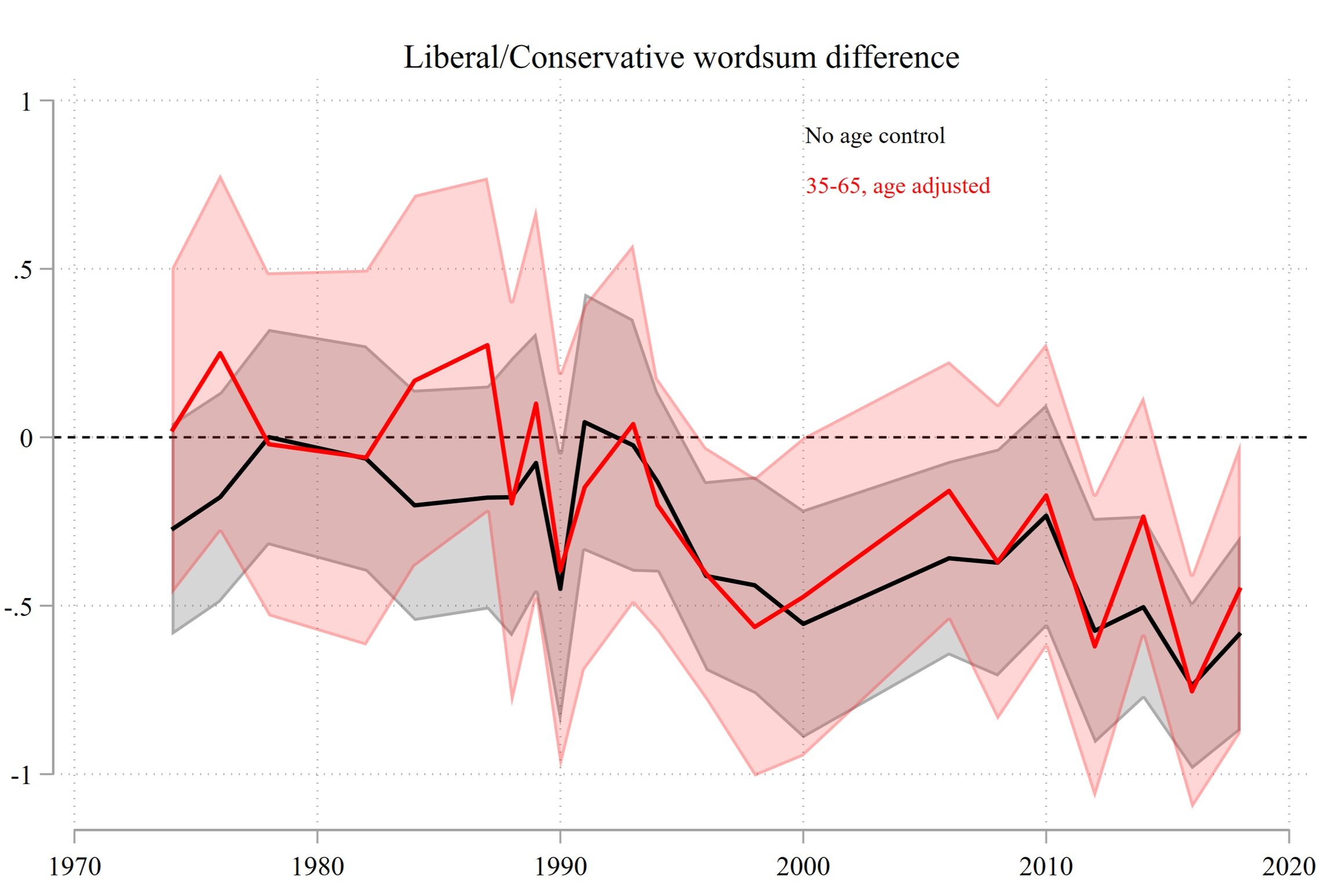

Before I move onto the implications of these trends in our flagship and why I think they reinforce my point above, let’s check out what’s going on with our peers. I decided to look at the number of articles published by year in American Economic Review, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Review of Economics and Statistics, American Political Science Review, and American Journal of Political Science. I did the same thing and collected their article information from Web of Science, restricting attention to articles and proceeding papers.

Results are below, showing the percent change from the mid 1990s.

Caveats: there is some weirdness going on in recent years. I think some journals, especially APSR and AJPS, were loading forthcoming papers for 2021 into the year 2020. So I’d discount the sharp rise of the two political science journals in the last year. AER wasn’t cataloging articles in the last two years for me, so I cut these out.

Most important conclusion: our peers aren’t shrinking their pies. The exception is QJE. QJE will publish 40 articles and 40 articles only, by God. Set your watch to it. Similarly, RES had a little bit of exuberance in the 2010s, publishing 25%-50% more articles than in the mid-1990s, but they’re returned to their earlier levels in recent years. The closest comparison is stability compared to sociology’s shrinkage.

AER, AJPS, and APSR have increased the number of articles published. Like I mentioned above, I don’t totally trust the last AJPS/APSR years. But they’ve increased their publication to about 10%-15% more than the mid-1990s, or from about 55 to 65. AER has rocketed their publications up by about 50%, while APSR has increased by about 20% since the mid-1990s. Importantly, after a dip in the 2000s, it looks like APSR is really pushing to increase the number of articles published.

That leaves ASR and AJS really standing out as a shrinking or stagnating flagship pair. Rather than shrinking by about 20%, perhaps sociology’s flagship journals should have increased their publication rates by 20% from their mid-1990 rates? I think that’s totally reasonable.

Why does this matter? Here are some of my initial thoughts.

I’m not convinced that it makes sense to talk about proportional representation inside of a shrinking pie. It appears that our discipline is perhaps unintentionally creating an artificial scarcity of top publications. Put alongside the growing population and publishing expectations of the discipline, it seems like the central issue is the likely growing size of good articles, many written by women, that should be published in these journals, that likely would have in previous decades, and may have been published if our discipline acted like our neighbors.

Let me phrase it this way: what would you think if ASR and AJS decided to jointly publish one article per year? Say they made the announcement tomorrow and did all the necessary behind the scenes coup work to make it a permanent change. Now, let’s say that I came along and said, “OK, what’s really important now is to count the number of first generation college students who are represented in AJS.” What would your reaction be? Maybe you’d think I was a little silly. The real issue is that these journals are doing ridiculous and unnecessary narrowing of top sociology research produced!

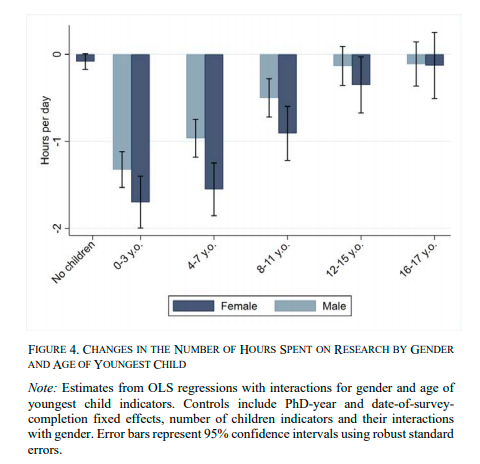

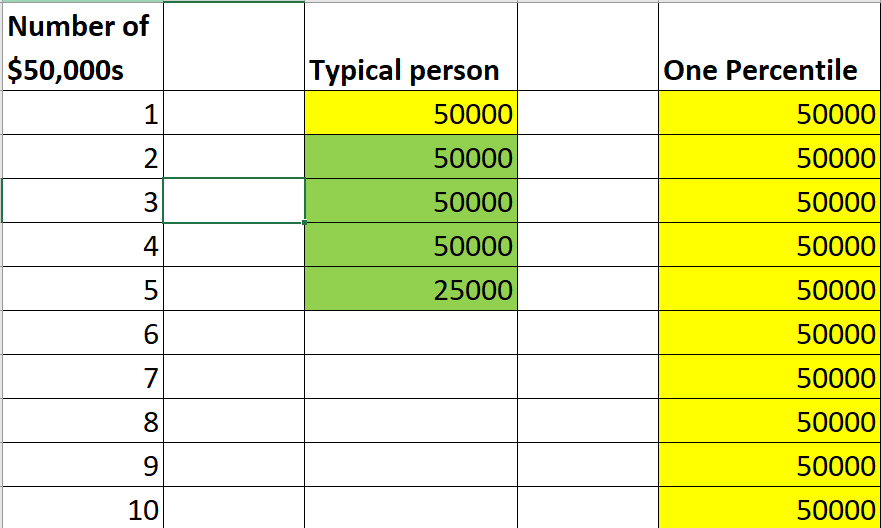

Let’s focus within gender:

Cohen’s focus is on the gender dynamics of AJS. About 33 articles published in AJS these days. The problem is that about 30% of authors are women instead of 50%. That is functionally saying, there should be 6.5 more articles published by women annually in AJS, or an increase from 10 articles to 16.5 articles.

If we aimed at balancing the gender ratios within the current shrunk pie, that would mean that the AJS authorship of the 33 annual articles would increase from 10 to 16.5. For ASR, the increase would be from 17.6 to 22. That’s a total increase of 11 flagship articles per year for women, and 38.5 flagship articles written by women per year.

Let’s say that we instead forced the same gender imbalance that currently exists but increased the number of AJS / ASR articles by 20% from their mid-1990s levels. That would increase their total publication numbers from (AJS) 33 to 43.2 and (ASR) 44 to 64.8 (these are much larger increases than from contemporary annual publications because the increased rates are based on mid-1990s levels, so they’d also remove the decline in recent decades). 30% of AJS articles and 40% of ASR articles in this larger stock translates to 13 AJS articles and 26 ASR articles.

In both cases—balancing gender ratios and expanding the pie but forcing the current gender imbalance to be maintained—you would end up with about 39 flagship articles written by women. But the big difference between the two: if you just mess with proportions in the current shrunk pie, the increase of female representation corresponds one-to-one with a decline of men’s published articles. In contrast, if you expand the pie, you end up with the same number of articles written by men, the same increase of articles written by women, plus an additional 20 flagship articles per year. I asked that these extra 20 articles be entirely allocated to men to maintain the current observed gender imbalance. But if you did literally anything more than nothing to address the gender gap, you’ll get way more female representation among flagship publications. More importantly, you would get women publishing flagship articles who would be locked out from today’s shrunk pie. You also avoid the uncomfortable situation where female representation would be created through a process that reduces the probability of men publishing in flagship journals in an era of reduced probability of publishing in flagship journals. I think this is very much what Altman was talking about with the problems of zero growth.

Let’s also think about the implications of a shrunk pie for what we’re saying about our contemporaries in the discipline. If we don’t increase the pie, we are forced to make an uncomfortable argument. With an increase in PhDs, an increase in women’s representation in sociology, and an increase in churning of paper writing and submission, the stagnation / narrowing of flagship articles, our discipline is structurally arguing, “young female sociologists today are writing less worthy flagship articles than young female sociologists 25 years ago.” I strongly disagree with this sentiment.

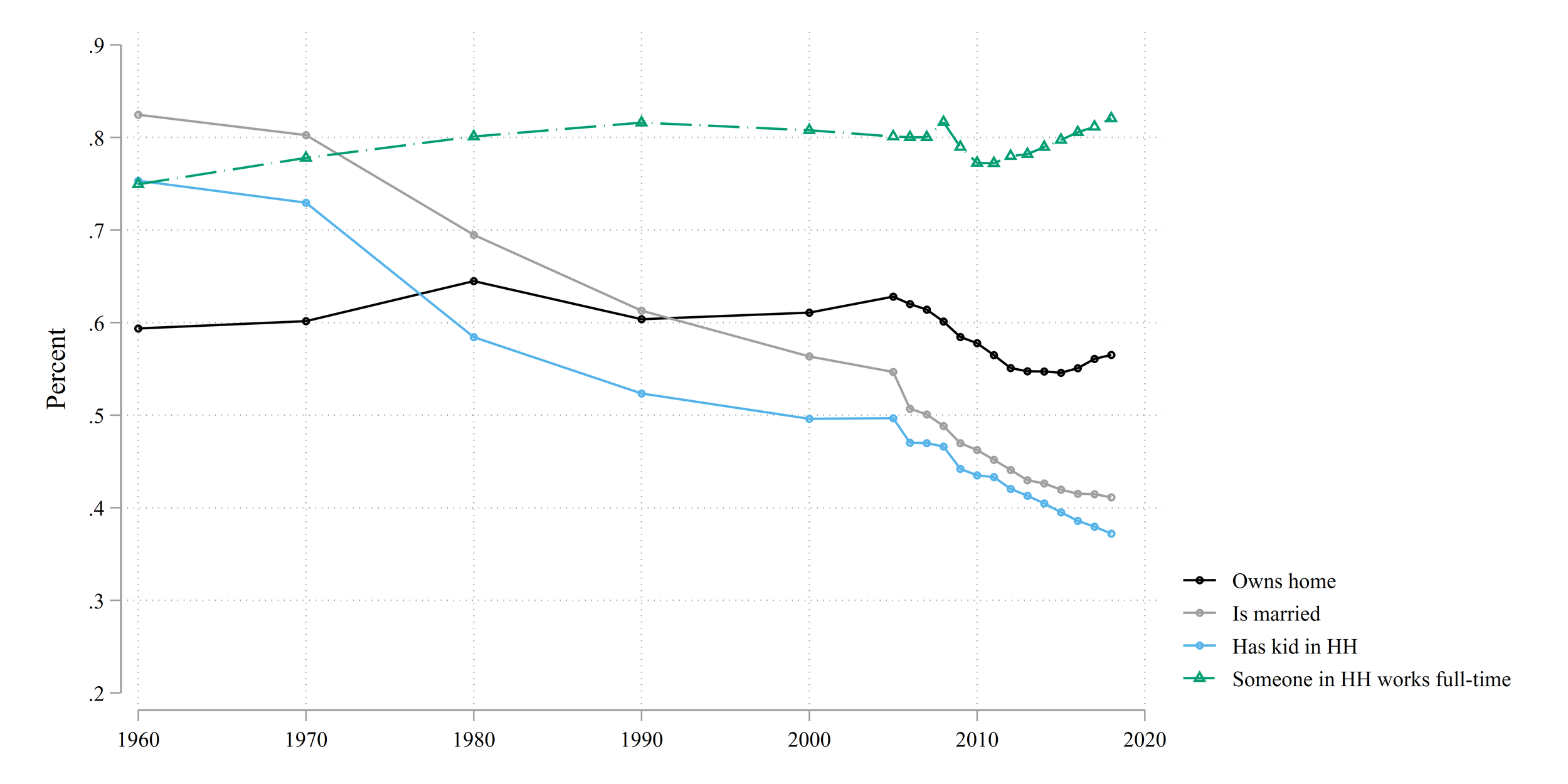

Let me hammer this home. Between 1995ish and 2015ish, the number of sociology PhDs increased by 50%. Today, the number of ASR articles is 80% of its mid-1990s levels. The number of articles to get tenure increased from about 6.5 to about 11. Let’s just map out the implications of this change. But let’s apply the consequences backwards, which I think really underscores the problem.

Here we’re looking at a very basic conceptual setup. Let’s say there were 1,000 sociologists (soc’rs) in 1995. According to Warren’s study, our supply has increased by 50%. So in 2020ish, there are 1,500 soc’rs. In 1995, there were 50 ASR articles annually. Today, there are 40ish. That means that in 1995, there was one ASR article published per 20 soc’r. Today, there is one ASR article per 37.5 soc’r.

If we apply today’s ASR-per-soc’r rate to 1995, we’d have ASR publishing 20 articles annually, rather than 50. Let’s just take a quick look at one issue from 1995. Here’s the Table of Contents from an issue that I randomly selected.

There were eight articles published in the April issue. I’m asking you to apply the current ASR-to-sociologist rate to this issue and cut the number of articles down to four. Which four articles do you cut? Mind you, you’re likely making an existential decision for the authors, their place in the field, perhaps even their careers. Does Jo Phelan make the cut? Does Scott South?

OK, let’s get even more curmudgeonly. Let’s introduce the increased publishing expectations.

We keep the growth of soc’res and upweight the number of articles they need to tenure. We now see that there was one ASR article for every 130 soc’r-tenure publications. Today, that number is 412.5. Apply today’s rate to 1995’s ASR count, you get 16 articles published annually per soc’r-tenure publications. So you only get to keep 2.5 articles from the above issue of ASR. Which are they? Whose careers do you want to profoundly alter?

Perhaps you think that this is a silly exercise. But I think it highlights the massive squeeze created through a shrinking flagship.

In that squeeze, it’s hard to make a very valid argument of a just distribution of resources. Just as it is difficult to make a strong claim for resources in a zero-growth world without necessarily stepping on someone’s toes. Don’t focus on proportions in a declining journal. Increase the pie at least to mid-1990s levels, probably more. Then think about gender. Don’t ask for a battle of the sexes. Ask men and women to unite against a shrinking pie.

A bunch of other random thoughts, in no particular order:

I wondered if the declining article count in ASR/AJS was counterbalanced by increasing collaboration. But I don’t think that sociologists are particularly more collaborative than political scientists or economists. I’d wager the opposite, actually.

Increasing the pie would have a bunch of downstream benefits. Like, maybe it would cut down the needless churn of reviews across journals. Perhaps good research would get out faster. Perhaps it would let our best research get out into the world faster. Maybe it would cut down on the more trivial and needless aspects of reviewer work.

I really think this needs to be asked. Are sociologists today worse at writing ASR/AJS-worthy articles than 30 years ago? I think the answer is obviously no. But we are artificially saying so by shrinking the flagships in the face of growth.

I wonder if a shrinking pie has more gendered downstream consequences. Like, isn’t there research about gender differences in risk aversion, assertiveness, status seeking in employment, etc.? Like, men feel more confident and deserving, on average, to ask for a raise, etc? If we make publishing in ASR more like journeying to the south pole rather than publishing great research, perhaps we’re accidentally bending the incentive structure of tactics taken towards these outlets? Perhaps we’re amping up flagship publications with high risk / high reward, more narrowly pointed status, etc. Maybe we’re accidentally male-typing the decisions to publish here? Seems at least partially reasonable to me.

Expanding the pie at our flagship journals wouldn’t do anything about publishing expectations or the crumbling job market. But…um…oh God…maybe forget I brought this up. Great research wouldn’t help with that. But insofar as flagship journals signal high-quality research that helps develop the field and move folks towards tenure and promotion, it makes sense to have the pie match the size and productivity expectations of the discipline. Perhaps having a bigger flagship pie would also allow for more great research to be quickly produced, disseminated, and move the field, allowing for a more straightforward understanding of the utility of hiring a sociologist for an applied position? I don’t know. Maybe. I think this is the weakest point of this post.

I assume that the editors of a journal cannot simply snap their fingers and decide to publish more articles. While all journals necessarily have their ups and downs, I have had a high level of respect for the editors of ASR and AJS from the time these journals meant anything to me, from about 2009 to today. They have all seemed quite obviously smart, productive, competent, well-intentioned, holding good values, etc. So I don’t think the problems stem from bad, or even thoughtless, actors. I’m much more certain that there must be arcane contracts and rules and procedures and costs and jobs from major academic publishers that make for pretty significant barriers to adjusting publishing. I am also confident that major publishers and perhaps even the ASA would fight hard against major expansionary attempts among the flagships. So the easy part is probably convincing individual academics that we should increase the pie. The hard part would be to fight against the institutions and rules and laws and legal councils on retainer lined up behind the current system. I have no idea at all how to start handling that second, more important, fight.